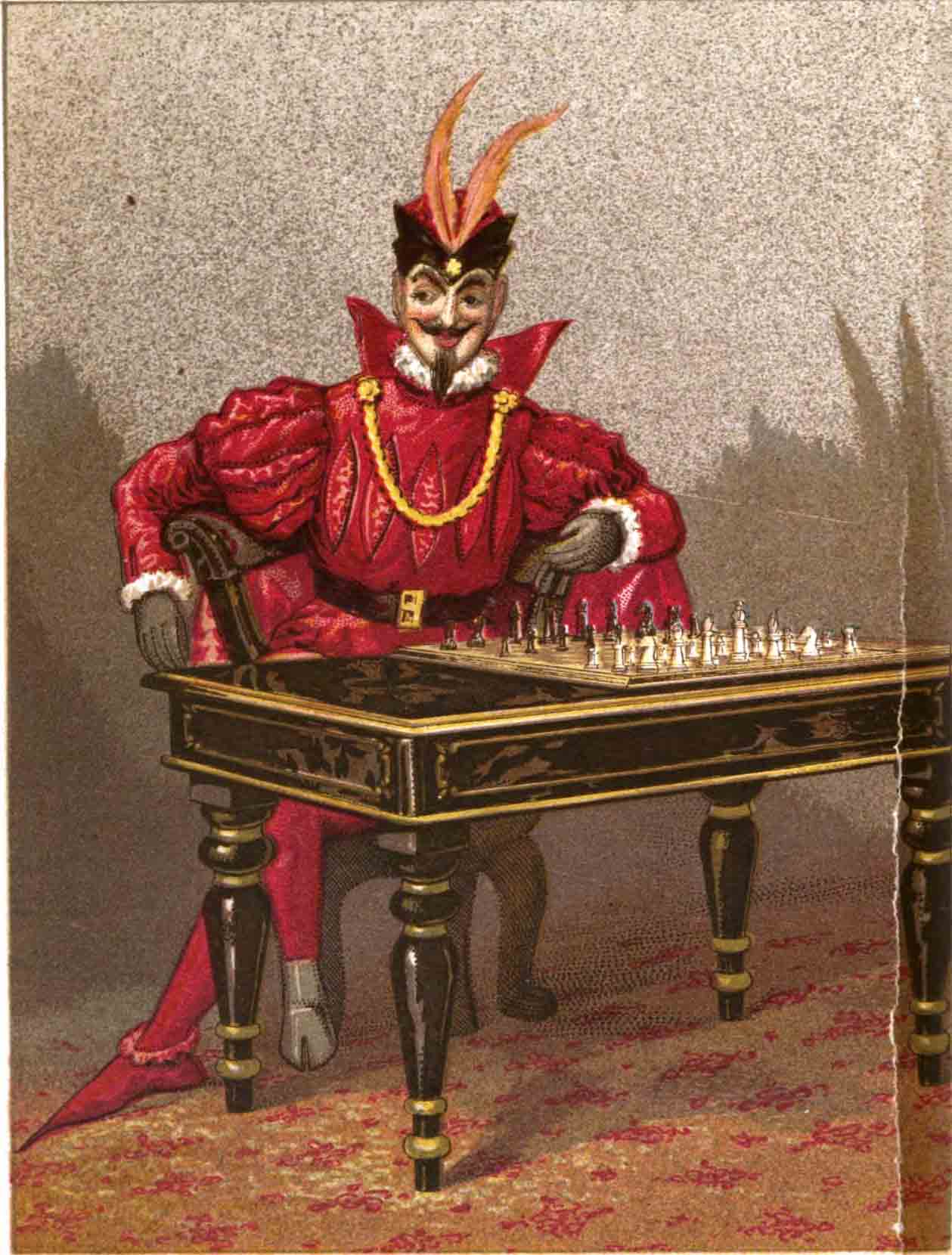

Mephisto the Magnificent

|

Charles Godfrey Gümpel, like the Turk director William Schlumberger, was from Alsace Lorraine. Using his skill for creating custom-made prostheses, he built the chess-playing automaton, Mephisto, over a 7 year period. From 1879 to 1889, Isodor Gunsberg directed the automaton which he did from a distance using electro/magnetic devices (as opposed to the Turk and Ajeeb who concealed the director within). In 1889, Jean Taubenhaus was the director. It's been said that Mephisto never lost a game.

Here's a game against the great Mikhail Chigorin!

________________________________

by

_______________________________________

A CHAPTER ON AUTOMATIC ANDROIDS BY The Inventor and Maker of the Automaton Chess-player "MEPHISTO." THE imitation of the actions and movements of organized beings by means of inanimate mechanism has at all times excited the ingenuity of man, and history records such attempts as having been made with more or less success. Merely to copy the "form divine of man" or animals proved no insuperable task: it resulted among the Greeks in the production of works of art, which at the present time still excite our admiration; but to put life into a marble figure—to make this product of human hands move and act like its prototype—why, this would place man on an equality with the gods ! While such ambitious ideas may have impelled the ancients in their attempt at the production of Automata (such as the walking statues of Daedalus and the flying pigeon of Archytas, &c., &c.), in more recent times it was the desire to excite the astonishment of the ignorant, the admiration of the learned, and to contribute to the amusement of the mighty. During the middle ages, when the physical sciences were still in their primitive development, when Theology, Scholastic Philosophy and Alchemy were the highest branches of learning to which the human mind could aspire; nay—even as late as the seventeenth century, the study of nature's phenomena (Astronomy perhaps excepted) was of rare occurrence; and hence any experiment, demonstrating the action of physical forces, and now made a plaything in our nurseries, was then looked upon as a wonder requiring the magician's wand for its manifestation. There must have been at that time something fascinating in the production of such mechanical toys, when we see the sage Roger Bacon busying himself with the construction of a talking head, Regiomontanus with a walking fly, and Albertus Magnus with a figure which opened the door when any one knocked; we have, however, too little definite information to guide us in our judgment as to the merits of their products. In more recent times we read a marvellous account of an Automaton group, constructed by M. Camus, for the amusement of Louis XIV., consisting of a carriage and horses, with a lady who alighted to present a petition ; and also in the Memoirs of the Academy of Science or 1729, of a set of actors representing a pantomime in five acts. No name has been more associated with Automata than that of Vaucanson, a French mechanician of the last century, whose fame was principally achieved by the invention of an Automaton- Duck, made entirely of brass, which imitated the quacking noise, moved its wings, picked up and swallowed food, and after having subjected this to a kind of digestion, expelled it. He next constructed a flute-player, a figure of life size, seated on a pedestal, which contained a set of bellows actuated by clock-work; whether, however, the sound was produced in the flute by the moving fingers and lips of the figure is highly improbable, but was more likely the result of a flute—or reed— organ contained within the body. Nevertheless, this figure deserved the name of Automaton, since the effect was achieved by self-acting mechanism, without the aid of human agency, beyond the winding-up of the clock-work. A little later we find an Automaton-Writer, constructed by a mechanician named Droz, in Switzerland, receiving deserved attention for its great ingenuity. The hand and fingers contained clock-work, by means of which the latter were enabled to write several letters in distinct and even beautiful outline. The son of Droz, however, eclipsed his father by the production of an Automaton representing a young girl, who played several pieces on the pianoforte, following the notes with eyes and head; and, when finished, rose from her seat and turned and bowed to the audience. This piece of ingenious mechanism excited great admiration in the Paris salons towards the end of the last century. None of these products of human patience and skill attained so great a reputation as did the so-called Chess-Automaton of Baron von Kempelen, a Hungarian nobleman at the Court of the Empress Maria Theresa. Animated merely by a desire to please his Imperial mistress, he produced a figure in the form of a Turk, seated at a chest or box, on which was placed a chess-board. This chest, to which the figure was permanently attached, moved about on castors, and when exhibited was wheeled into the middleof the room so that the audience could inspect it all round. Several doors of the chest were successively thrown open to show the machinery contained within; all was then closed, the clock-work wound-up, and play commenced—during which, however, no part of the interior was ever exposed. This Automaton played not one or several " set" games, but entered the contest against all comers; hence the great astonishment and curiosity it excited wherever it made its appearance. Long treatises were published on the great merit of this wonderfully-ingenious mechanism. Men of science, who ought to have been able to solve the puzzle, were sorely tried to say more than that this machine was an Automaton, that is: a machine producing by means of clock-work movements in a direction and manner, which in a human being required the guidance of the highest intellectual faculties. But was there ever any doubt about this machine being an Automaton ? Did not every part of the chest contain machinery, excluding the possibility of a human player being secreted within it; and as the chest or box had no direct communication with any part of the surroundings, how otherwise than by mechanism could this phenomenon be produced ? Such was and is, no doubt, the reasoning applied by the ordinary—even the educated and often scientific (?) observer. Nothing tests a man's higher grade of common sense and his thinking powers more than the solution of a question, which throws him out of his ordinary every-day track. Here is a phenomenon, to the explanation of which he cannot apply any or all the speciality of his learning; he is completely lost to give a sound and simple judgment, as he has to fall back upon his natural capacity for reasoning, and hence breaks down. With astonishment the audience surrounded this Automaton, and were lost in admiration of the ingenuity displayed by the inventor. So it was at the end of the last century; and whether popular common sense has made any progress since, we shall see as we proceed. The inventor of this "Automaton" never hesitated to speak his mind plainly as to the real merits of his machine. " It is," said he to his friends (citing from Geo. Walker's " Chess and Chess- Players"), "a trifle, not without merit as to its mechanism; but those effects, which to the spectators appear so wonderful, arise merely from the boldness of the original conception, and the fortunate choice of the means employed by me to carry out the illusion," which, interpreted into plain language, means that Von Kempelen never wished to palm off his Chess-player as an Automaton, placing himself thereby far above a critic in the "Leisure Hour" of January nth, 1879, who by his remarks endeavours to pull him down into the ranks of tricksters. When the machine had to serve other less scrupulous masters, it was presented, not as " a trifle, not without merit/' but as an Automaton playing an intellectual game by the intricate combination of machinery; whereas, in truth, a human being was concealed within the chest, and the merit of the whole contrivance consisted in the ingenious manner in which this concealment was effected in so small a space. Although generally looked upon with wonder and astonishment, yet there were voices raised to expose this so-called Automaton as a trick. Already soon after its first exhibition, a Mr. Philip Thicknesse published a pamphlet in 1785 with the object of "denouncing the Chess-playing automaton as a piece of imposition;" and cites an analogous case, which had, perhaps, put him on the scent:— "Forty years since," writes Thicknesse(see Geo. Walker's " Chess and Chess Players"), " I found three hundred people assembled to see, at a. shilling each, a coach go without horses, moved by a man withinsideof a wheel, ten feet in diameter, just as the crane-wheel raises goods from ships on a quay. Mr. Quin, the Duke of Athol, and many persons present, were angry with me for saying it was trod round by a man within the hoop, or hinder wheel; but a small paper of snuff put into the wheel, soon convinced all around that it could not only move, but sneeze too, like a Christian." Geo. Walker adds :— "We wonder how De Kempelenwould have met a proposition to throw an ounce or two of snuff upon speculation among his springs and levers ? " Mr. Thicknesse continues: "I saw the ermine trimmings of the Turk's outer garment move once or twice when the figure should have been quite motionless, and that a confederate is concealed is past all doubt; for they only exhibit the Automaton from I to 2 o'clock, because the invisible player could not bear a longer confinement ; for if he could, it cannot be supposed that they would refuse to receive crowns for admittance from 12 o'clock to 4, instead of from I to 2. Indeed M. de Kempelen had the candour to say to a certain nobleman in Paris who asked him to disclose the solution of the problem, 'Quand vous le saurez, mon prince, ce ne sera plus rien.' " After the Automaton's second visit to London (during which, for a time, Mr. Lewis, the famous Chess-Player, directed its moves), a solution of the enigma was published by a Mr. (afterwards the well known Professor) Willis, of Cambridge University, proving "by figures and drawings, that a man may be concealed in the chest, able to overlook the board through the stuff-waistcoat of the figure; having shifted his position in his lonely cell several times, while the different parts of the apparatus were being exposed successively to view." Before giving his own explanation of the Automaton, Geo. Walker makes the following very pertinent remarks :— "Our early reading supplies our memory with a bit of Sand ford and M e r t o n, in which one of the boys is deservedly reprimanded for taking the bread out of the mouth of the juggler, at the country fair, through neutralizing a portion of his legerdemain by public exposure ; and, for a somewhat similar reason, never should our good goosequill have dissected the Chess-Automaton without fair and sufficient cause. Still this demands explanation. The two cases of the juggler and the Automaton, placed in juxtaposition, are by no means analogous. The conjuror at once honorably admits that he works by sleight of wrist,—by confederacy,—and also by previously combining certain laws of nature, and established causes of effect, to produce corresponding results unknown to the vulgar. The Chess-Automaton, on the other hand, stood before its patrons with a lie in its mouth; dipping his timber fingers saucily into the pockets of the lieges, under most foul and false pretences. "The man who really played the Chess-Automaton was concealed in the chest! Such, in half-a-dozen words, is the sum and substance of the whole truth of the contrivance ; but the manner in which his concealment was managed is as curious as ingenious. He sat upon a low species of stool! moving on castors, or wheels, and had every facility afforded him of changing and shifting his position, like an eel. While one part of the machine was shown to the public, he took refuge in another; now lying down, now kneeling ; placing his body in all sorts of positions, studied beforehand, and all assumed in regular rotation, like the A K c of a catechism. The interior pieces of clock-work—the wheels, and make-weight apparatus—were all equally moveable, and additional assistance was thus yielded to the fraud. Even the trunk of the Automaton was used as a hiding-place, in its turn, for part of the player's body." The appended wood-cuts (figures i to 5), taken from Professor Willis' book, will give some idea of the manner this was effected:—

The vast apparatus of wheels, springs, levers, &c, were the dust thrown into the eyes of the public; and the winding-up of the machine, by Maelzel, was commented upon by Professor Willis in the following remarks :— " In all machinery requiring to be wound up, two consequences are inseparable from the construction. The first is, that in winding up the machinery, the key is limited in the number of its revolutions; and the second is, that some relative proportion must be constantly maintained betwixt the winding up and the work performed, in order to enable the machine to continue its movements. Now these results are not observable in the Chess-player ; for the Automaton will sometimes execute sixty-three moves with only one winding up ; at other times, the exhibitor has been observed to repeat the winding-up after seven moves, and even three moves ; and once, probably from inadvertence, without the intervention of a single move ; whilst in every instance the key appeared to perform the same number of revolutions, evincing, thereby, that the revolving axis was unconnected with machinery, except, perhaps, a ratchet wheel and click, or some similar apparatus, to enable it to produce the necessary sounds ; and, consequently, that the key, like that of a child's watch, might be turned whenever the purposes of the exhibition seemed to require it." The reader who has followed so far, will be ready to join in the remarks of Mr. George Walker, when he says — "A man inside will most assuredly never again work the charm, but advanced as science is, during the present generation (written in 1850) a clever mechanician could easily and successfully vary the deception." Well, and has not this been done ? Is not the Automaton Chess-player, lately exhibited at the Crystal Palace and other places about London, worked by machinery only ? Is not the whole of the chest and figure exposed to view, showing the impossibility of a player being concealed within it; does not the attendant tell you that the machine-figure plays Chess by machinery, and does he not wind up the clockwork, which moves the arm, &c. ? And, above>11, does not the daily Press uphold this Chess-player as an Automaton, and support the public in the belief that it is a most ingenious piece of mechanism, deserving of the highest admiration? These questions, ending with the finishing sentence, " I have seen it with my own eyes, and cannot believe otherwise P—are not fictitious, but were addressed to the writer of this in the year of Grace, 1878, by men who expressed themselves and behaved like educated gentlemen. And even men of scientific position in society have shown their belief in this Automaton by exclaiming, "The secret has been found out Now ; there's a player inside the figure, who can see the board and men!" Yes, and see the opponent, and can hear every word said in front of the figure. (See an article on Automatic Chess and Card-Playing, in the 'Cornhill Magazine," vol. xxxii., page 589, November, 1875.) Setting aside the possibility or impossibility of a true Chess- Automaton, the ordinary circumstances, accompanying the exhibition of the figure, were such as to rouse the suspicion of any thoughtful observer. The various doors successively opened, exposed to the audience only a small portion of the box and the figure, which were " almost big enough to contain two players ;" and very little machinery, easily removed, sufficed to arrest the physical eye of the gaping visitors, not one in a thousand of whom would penetrate with his mental eye beyond and to the side of the exposed sham-mechanism. When once the doors were shut, and play had commenced, even a close approach to the front of the figure, to obtain a pee pat the working machinery, was prohibited; and as for an exposition of this exquisite mechanism, this most ingenious contrivance of which even a Babbage might be proud, ah! that was impossible while the figure was playing. Why, of course, someone might steal the idea and enter into competition with the original inventor, and so deprive him of the rewards of his skill and patient labour! It does not occur to these short-sighted advocates that the idea might be stolen—if that were at all possible—whether the machinery was shown at rest or in motion; and in fact, it was stolen in 1876 at Berlin, and the thief had the audacity to offer for sale and actually sell Chess Automata at £30 a piece, in consequence of which these self-acting Chess-Players were exhibited at a great many places and country fairs in Germany. The Press in the chief towns and cities, where the original was shown, did not hesitate to expose the showman's trick, and pronounce this ingenious mechanism as a base imposture. There is a moral attached to this, which the reader can extract for himself after the following remarks and with the help of figures 6 and 7:— *

"These sketches are copied from photographs bought at the Crystal Palace and the dark outlines of the player were added in accordance with a; description, given by a Chess-player of note, who "acted the Automaton" for a considerable time in a similar figure.

If a man were to take his seat opposite you to engage in a Game of Chess, were to cover himself with a fancy dress, crown himself with a false head, and then were to ask you to believe him to be a Chess-Automaton—well, dear readers what would be your reply? It is certainly not flattering to the state of public education that so simple a trick should for years have eluded the understanding of the mass of the people, and it proves that " the use of the imagination " is not only needed in scientific, but also in matters of every-day life. The faculty of the mind of seeing more than is presented to the eye is, no doubt, rare 5 the individual judgment is set aside for a dependence upon authority; What do the papers, what does Mr. So-and-so say about it ? is the first inquiry, and not: How can I explain this phenomenon? No special knowledge of Chess or of Mechanism is requisite to answer the question about the possibility of a true Chess- Automaton, that is : a self-acting machine which shall, by means of mechanism only, and the total exclusion of all external aid, perform the movements of a Chess-player on the Chess-board, with the definite object of forming all the combinations according to the rules of the game, and under all the varying circumstances of weak and strong play. Such a machine is an impossibility. The late Mr. Babbage, with the versatility of a superior mind, may have considered such an achievement as possible in theory; but practical reasons will easily show the futility of attempting the execution, or even the design, of such a mechanism. We may have at the commencement of a game only 20 possible moves to make; but as soon as the game is developed, the combinations, that have to be provided for, are so numerous as to defy all possibility of arranging the mechanism to produce them. A simple calculation will show. The Chessmen, although 32 in number, may for simplicity's sake be reduced to 12 (viz., King, Queen, Rook, Knight, Bishop, and one Pawn of each colour—leaving the other Pawns out of the question); while one of these 12 pieces stands on No. r square, either one of the other it may stand on No. 2 square, so that we can make n changes on No. 2 square, for each piece placed on No. i; or for easier calculation, let it be 10 changes, hence on the two squares, we can ring 10 x 10=100 changes. We have on the Chessboard 64 squares; since, however, the two Kings can never stand on adjacent squares, and as a King cannot be in check by more than two pieces at a time, &c., &c., we shall have to reduce the number of squares to, be it one half, 32. To obtain the number of combinations which can be formed by the Chessmen on these 32 squares, we have to multiply the number 10 by itself 31 times and the result would be given by writing 32 noughts after i (100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000). Similar combinations may happen at different times on different parts of the board; still, provision must be made for the arm to make the required moves on either part; the same combination of pieces on the board shifted only one square, requires in the mechanism a special arrangement for such altered position ; so that the above number of possible combinations, for which the mechanism must be constructed, is certainly not too high. The assumption that the number of openings are limited and that the machinery can be " set" for the best moves, is very easily " up-set'' by a Tyro putting his Queen en-prise, to say nothing of a false move; and unless the Automaton could take advantage of the first or correct the latter, the Game would soon arrive at a chaotic state. A very amusing result is arrived at when inquiry is made into the time necessary for constructing the mechanism. This latter may be compared with a Jacquard's loom, in the cards of which (in this instance of metal) one hole is to be marked and drilled for each possible position of the men on the board. Let a workman mark and drill 1,200 holes per hour—12,000 per day of 10 hours ; let him work 300 days in the year, and 50 years of his life, drilling 180, or in round numbers, 200 millions of holes during this period, then we should have to write 23 noughts after 5 (500,000,000,000,000,000,000,000) to obtain the number of workmen, whose lives' labour would be absorbed in marking and drilling the number of holes required to meet the above combinations. No! a veritable Chess-Automaton is an absolute impossibility; but this offers no justification for resorting to a base deception in the attempt at constructing a Chess-playing figure—an Android (a figure of the form of man) which shall to all external appearance be automatic, i.e., self-acting. Disgust at the deception played by these so-called Automata was the incentive to the invention and construction of "Mephisto." He is a figure of life-size, seated in an arm-chair at an ordinary table, on which a Chess-board is placed. There is nothing extraordinary in the latter except that each square has a slight indentation, into which the base of the Chessmen fits, to ensure these being placed in and prevented from shifting out of the centre of the square. The men are Staunton pattern, like ordinary Chessmen. The figure is slight, unencumbered by any loose drapery, sits fairly on the chair, and is bolted to the table, to enable the arm, which is about 28 inches long from the shoulder- joint to the end of the fingers, to reach across the board. The movement of the arm is made in so natural a manner that it cannot be better described than human-like. When taking one of his opponent's pieces, "Mephisto " first removes this from the board and then places his own in its stead. The opponent's pieces, deposited by him on the table, he can take up again, and replace them on the board—as, for instance, when giving back the Queen which an opponent had inadvertently lost. At the opening of the game he can play very quickly, making four or five moves in reply to his opponent's rapid play, without resting his arm; and, although sightless, he is quick, generally, in perceiving his opponent's move. That these effects are really produced by the figure alone, without the aid of a confederate, or by any possible reflection of the board in any part of the room, can easily be proved by covering the front of the figure as also the board and men, while the opponent makes his move—such as putting his Queen en- prise, or taking one of " Mephisto's " pieces, or making a false move, thereby forcing " Mephisto" to a definite reply. This heightens the mystery surrounding the whole, since it becomes a question—how does the " guiding intelligence " see or know the moves, and how is the arm and hand directed to grasp the piece and deposit it on the proper square, which must be done with great precision; and the puzzle presented by "Mephisto" is complete, when, during play, every part of the figure and furniture can be closely inspected—so unlike all other so-called Automata, with the performance of which even an approach in a certain direction interferes. It has taken the inventor the greater part of his leisure time during seven years to design and direct the construction of the machinery ; and when finished he exhibited it for several months at his own house, during which period "Mephisto" played many Games against various Metropolitan Players of note. These Games, published in the columns of The Field, Illustrated London News, Land and Water, Westminster papers, &c., found their way into other papers all over the world, so that "Mephisto's" name as a Chess-player soon spread to the Continent, to America and to Australia. Since he has made his appearance in public, he plays more an off-hand game, and rather resigns a contest than to continue a tedious end-game with a slow player. The whole phenomenon presented by "Mephisto" appeals to the understanding of all educated persons, whether Chess-players or not; the frequent visits paid him by those who have once watched his movements prove the fascination he exercises upon his audience; and since the inventor represents "Mephisto" simply as an ingenious scientific puzzle, it removes this Android far above those so-called Automata, depending in their effect upon deception, and which to show in their proper light is his mission.

|